A project from Avik Das in the lesson.

Mainly, we implement a 3D renderer with the knowledge of computer graphics.

I have a related project on 3D, WebGL and Computer Graphics, which helps me a lot to understand this lesson.

RayTracing and Rasterization

There are two approaches to solving the visibility problem.

The conceptually simple approach is ray tracing, which simulates light rays reaching the camera by sending out rays from the camera, then tracing its path as it travels to a light source. This maps well to how light physically travels in the real world, making it simple to simulate real-world effects such as shadows and reflections. These effects are collectively known as global illumination.

However, this simulation is slow. An alternate approach is rasterization. In this approach, we first project the geometry onto the image plane, then work directly on the perspective-corrected representation of the geometry. This approach can be implemented more efficiently, but at the cost of increased complexity. Global illumanation effects need to be special-cased one by one, often requiring multiple rendering passes and pre-computation ("baking").

Ray tracing is usually used for offline rendering, such as in Pixar films, and rasterization for realtime graphics, such as games. The latter is the approach used by GPUs.

How light travels in ray tracing

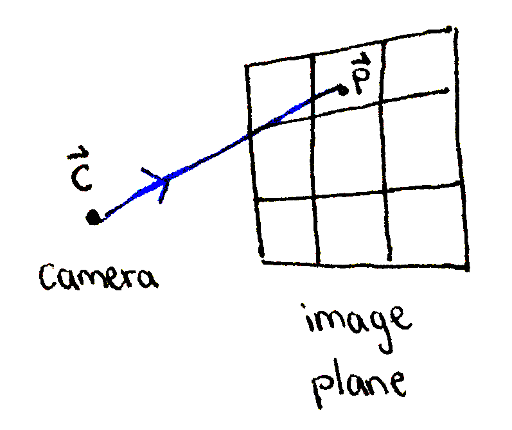

In ray tracing, we cast rays from the camera out into the world and see how they end up at the light sources.

But how many rays do we cast?

To answer this, we divide the image plane into small regions, one corresponding to each pixel in the output image. Then, we construct a ray starting at the camera and passing through the center of each region.

Simulating illumination using Phong shading

In general, this is a hard problem, but we can approximate it with local illumination.

We will consider only the object and the lights in the scene, ignoring the effects of other objects in the scene. One way to do this is with the Phong reflectance model, which consists of three parts:

-

The scene contains some ambient light: This approximates the light coming from other objects using a constant term. The object reflects some portion of this light, represented by a proportion.

-

For each light in the scene, the object reflects some portion of the light's intensity. This is the diffuse component. A diffuse object scatters light in all directions.

-

For each light in the scene, there may also be a specular highlight that depends on the viewing angle. This highlight occurs because a reflective surface reflects light in a particular direction. The more aligned the vector to the camera, the brighter that point appears to the viewer.

Casting rays to render shadows

One piece of geometry might block light from reaching another, resulting in a shadow.

Suppose we are trying to find the color at a certain point on an object. We will do the following:

-

Cast a ray from that point to each light source.

-

For each ray, we will perform an intersection test with each other piece of geometry in the scene.

-

If the ray intersects with any geometry before reaching the light source (intersecting at 0 < t ≤ 1), the point is in shadow from that light source.

If the point is in shadow from a particular light source, we will ignore the diffuse and specular contributions from that light source when computing the Phong illumination.

We will continue including the contributions from any lights that are not blocked by other objects. We will also always include the ambient term. This term approximates indirect lighting, ensuring shadowed areas are not completely black.

Recursive ray tracing and reflections

Light bounces of all geometry, but different materials bounce light in different ways. Some materials are highly diffuse, meaning they scatter bounced light in many directions, sending a little bit of light in each direction. In contrast, some materials are highly reflective, meaning they send bounced light in one direction. Many materials are a combination of the two.

We add in one more term to the Phong illumination model: the reflected light weighted by a reflectivity constant. Usually, the larger reflected portion is, the lower diffuse protion is, and vice versa.

Recursive ray tracing is also the basis of simulating refraction, where light passes through a translucent object. While we will not implement refraction rays in our ray tracer, the general principle is mostly the same as the reflectance rays, differing only in the direction the refraction ray is cast.

Distributed ray tracing and anti-aliasing

The images produced by our ray tracer so far have jagged edges around the geometry in the scene. This is because we have only cast one ray per pixel. That ray either sees some geometry, or it doesn't, leading to sharp transitions. This is known as aliasing, because, due to the imprecision of sampling once per pixel, two different scenes may produce the same output image.

The solution is to cast multiple rays per pixel—each at a different point inside the pixel—then average the results together for that pixel. This approach is known as distributed ray tracing, where multiple rays are cast and the results averaged.

When used to avoid aliasing, the technique is called supersampling antialiasing, or SSAA. The increased quality comes at a cost. The number of rays cast in total is multiplied by the number of samples per pixel, resulting in doing that many times more work for a single image.

A related technique is multisampling antialiasing or MSAA, where multiple samples are only taken at the edges of the geometry. This alleviates the performance hit of supersampling antialiasing.

The general principle of distributed ray tracing can be applied to simulate many photorealistic effects:

-

By distributing the rays through time, a moving object will be subject to motion blur.

-

By distributing the origin of the camera ray over a 2D interval, depth of field can be simulated.

-

By modeling a light source as a 2D interval and distributing shadow rays over that interval, soft shadows can be rendered.